Shop Classes Return — with a 21st-Century Twist

Teaching life skills such as high tech welding could be one antidote to the economic crisis.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.

Students in auto-body shop in the Tucson Unified School District, in Tucson, Arizona, don't just learn how to change oil or hammer out a dent. They use computer diagnostic equipment to fix cars, and learn the green technologies of hybrid vehicles and hydrogen fuel cells.

For kids in the district's welding classes, a water-jet cutter not only represents the latest in high tech cutting equipment, using high water pressure to quickly slice through metal, it also teaches the math needed to program the machine.

And in construction classes, students still build -- in between lessons on résumé creation and proper work-site communication.

Welcome to the 21st-century shop class. In pockets around the country, a retooling of classes in career and technical education aims to give students job training, exposure to new technologies, and windows into different careers. The resurgence of shop has been slowly taking place nationwide over the last several years, partly in a response to industry demand. When shop classes began a decline in the 1970s, coinciding with a push toward college-bound classes, so did the number of young people entering skilled trades. Now, industries facing a worker shortage are pushing for the classes' return.

Not Your Father's Shop Class

The new incarnations of shop are a far cry from the old, in large part because technology has evolved so much. Today's classes incorporate a range of those abilities widely promoted as 21st-century skills, involving technology, communication, and collaboration.

"It's not just getting out and working on the cars," says Aaron Ball, director of program development for the Pima County Joint Technological Education District, which helps fund career programs in several Arizona districts. High technology is a key part of automotive education -- and work -- these days: Today's cars can have as many as 50 microchip-size computer processors in them.

In Tucson's auto-shop classes, teachers create a problem somewhere in a car -- or in special stand-alone training units that represent a car -- and students have to figure out what's wrong. It teaches them today's automotive technology, as well as critical-thinking skills and teamwork, says Kathy Prather, director of career and technical education for the district.

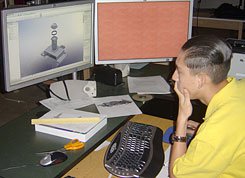

In some of the district's design and drafting and machine shop classes, students use a computer-assisted-design program called SolidWorks, in which they can create three-dimensional drawings. And the welding program's water-jet cutter (besides adding a cool factor for students who've seen one on the television show West Coast Choppers) requires users to plot out the settings on a computer graph.

"Students are loving the new technologies," Prather says. "These classes bring the academics to life. They reinforce and teach the academics to those that learn better though applied methods."

Preparing Students for Tomorrow's Jobs

Of course, they also prepare students for jobs. The need for trained technical workers didn't go away when shop classes dropped out of vogue. In fact, it is rising, according to the latest job-outlook report from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. It predicts, for example, that there will be more machinist jobs than skilled workers available over the next seven years. And employers say they already have a hard time finding adequately skilled auto technicians and mechanics -- jobs expected to increase by about 110,000 by 2016.

Teacher Hollis Simmons created a building-trades program at Tucson's Catalina Magnet High School at the urging of the Southern Arizona Home Builders Association. Simmons tries to give his students a range of skills they'll need on the job. In addition to actual building -- students design and build sheds, as well as learn to do electrical work and hang drywall -- he teaches soft skills, such as appropriate communication on the job and how to create a résumé.

Catalina senior Jerry Soto landed a job last summer with a local construction company, making ductwork and other materials for buildings. "Mr. Simmons taught us how to present ourselves for a job," Soto says. "He taught us how to dress up for a job." Plus, when Soto started working, he was already well versed in the tools used because he'd had practice in class. When he graduates, Soto plans to work for the company full time.

Soto found Simmons's shop classes so useful that he chose to attend an extra course before school. "I put the extra effort in trying to learn more so when I went to any company, I knew more than just your average Joe," he adds.

Not every student is truly college bound, argues Simmons, who says these classes meet an important need for those students. Karen Ward, of SkillsUSA, a national organization that supports construction, automotive, and other career programs in high schools and postsecondary schools, echoes that point. "The economy really ramps up the idea of career programs," she says. "The idea of everyone going to Harvard isn't going to work when the price tag is so enormous."

Perhaps for this reason, students themselves are demanding a resurgence of shop classes in places like Massachusetts, where Ward says automotive classes have "students coming out of their ears." To meet the demand, she adds, several Massachusetts high schools are investing in updated labs for existing classes and adding new shop classes where they can.

Nevertheless, today's shop classes, like the multitude of other career and technical education classes offered around the country, also emphasize postsecondary education. The programs in the Pima County technical-education district push students into apprenticeships or certification programs or offer college credit. Teachers in Tucson also are developing materials that show how students can continue their education, based on what career classes they take, after high school. Worcester Technical High School, an academy school in Worcester, Massachusetts, with programs in construction, offers college credit through two-year and four-year colleges.

But whether students are looking for serious job training or a curriculum-enhancing elective, these hands-on classes offer them something we all need: life skills. As Simmons tells students, "You're going to own a house at some point in time, and the stuff I'm teaching you is something you can use."