Using the Arts to Synthesize Student Understanding

Uncover how you can use the arts to both meet your arts standards and deepen academic learning.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Overview

Sharanya Sharma’s second-grade class at Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, DC, surveyed people at Reagan National Airport to find out what they knew about how airplanes fly. They discovered that most people don’t know how planes stay in the air.

“Our problem,” says Stuart, one of the students, “is people at the national airport don’t understand the physics of flight, even though they’re about to get on planes.”

“We’re trying to teach people how to learn the physics of flight,” adds Paz, another student.

Sharma partnered with Leah Quinter, an elementary visual arts teacher, to teach the physics of flight. Their final product: a large, whole-class acrylic painting that shows the four forces of flight—thrust, lift, gravity, and drag. The painting will be displayed at Reagan National Airport to solve their problem in science: teaching people at the airport how airplanes stay in the sky.

“Particularly in the elementary school, we have a heavy focus on arts integration as it relates to our expeditions—[in depth, content-specific, problem-based learning explorations that are a part of expeditionary learning],” explains Tonia Vines, a dramatic arts teacher. “Twice a year, we integrate social studies or science content with drama or visual arts.” Students have 45-minute visual arts classes twice a week for half the year, and then take drama classes for the rest of the year.

“Arts integration is about reaching as many students as you can,” explains Sharma. “Being able to have that tactile experience of flinging paint at the paper, or pouring paint down a paper to see how gravity works, it connects what they’ve learned in art to their everyday experiences, instead of just that one classroom experience.”

How It's Done

Start With Research

If you’re uncomfortable with your partner's academic or arts subject, try studying the content. “Through researching, you can start to think about ways to integrate,” explains Quinter. She suggests that you ask yourself:

- Where does this match my subject?

- Where does this match my content areas?

- What are my goals for my students, and how can we reach those in both subjects?

Plan Together

Share with each other what your standards and learning targets are, look for common goals, and brainstorm topics, guiding questions, and a final art product that can both deepen the academic learning and teach the art content. At Two Rivers Public Charter School, during the three-week orientation each summer, teachers have two 2-hour sessions to co-plan, and when school starts, they have two or three 1-hour sessions during professional development. They continue to plan after school, over email, and via Google Docs. Here is the visual art unit map (PDF) Sharma and Quinter created connecting the four forces of flight to art.

Test Your Plan

Once you’ve decided on a final art product, make a model. “We believe in testing it first ourselves,” says Sharma. “If we’re having fun and learning from it, then it might work with our kids. If we’re bored, then we go back and start again.” Creating a model not only gives you experience with the process but also shows your students an example of what great work looks like and what they’re striving for.

Build on Your Strengths and Weaknesses

If you discover a product that resonates with your students, repeat it. “Sharanya and I would discuss the content and what was strong about what we’ve done in the past, and then where we’d like to push that thinking further,” remembers Quinter. “What we were missing was cementing the two classes together and a lot of debrief time.” With shorter visual art classes, students spent more time on making art and less time discussing the connection to their science. To reinforce what the students have just learned in art or academics, Sharma and Quinter:

- Use common vocabulary.

- Use the same reference materials.

- Ask their students what they learned that day in the other class.

“She’s asking them what they did in art, and I’m asking them what they did in science. That’s been helpful,” reflects Quinter.

Outside of reflecting with each other, Sharma and Quinter also get feedback on their instructional planning from a group of teachers who analyze their students’ work—discussing where their students are in their understanding, what’s being assessed, and what next steps Sharma and Quinter can take to better reach their learning targets. (See Analyze Student Work to Inform Instruction and The Power of Vulnerability in Professional Development.)

Integrate the Arts Through Experiments

A common challenge with arts integration is ensuring that you’re meeting your arts standards. “It’s not just an add-on or something fun at the end,” emphasizes Quinter. “It’s something that truly deepens their understanding of that content, and also the arts.”

“This year, they used the forces themselves to make the art,” says Sharma, “where in past years they would draw a picture of that force at work and incorporate that into their final product, which was a booklet incorporating illustrations of the physics.”

Along with their collaborative acrylic painting this year, Quinter’s class did three experiments:

Three Experiment Ideas

Marble Experiment: Quinter’s students started with a copier paper box lid. They put paper, two to three drops of tempera paint, and a marble inside. Students grouped into pairs, moved the lid around, and watched how the marble interacted with the paint.

“We rolled the marble around, and it made the lines of thrust to go forward because thrust means to go forward,” explains Paz.

Salad Spinner Experiment: “They placed circle-shaped paper at the bottom of the salad spinner,” explains Quinter. “Dripped six to eight drops of liquid watercolor inside, closed the lid, and spun it—their arms demonstrating thrust to power the spinner, and the paper conveying drag lines visible as the paint was pulled. They could go fast. They could go slow. When they opened the lid, they observed what happened.”

Waterfall Experiment: In pairs, Quinter’s students poured watered-down tempera paint onto paper attached to a clipboard. “They would manipulate the board to see if it would change the reaction of the paint,” says Quinter. “What they would often discover is that it did not, that gravity was always pulling the paint down, no matter how they spun the board.”

During your experiments, ask your students guiding questions. Ask them what they’re seeing and have them explain why. Challenge them -- say, “Is it this? Is it not that?” advises Quinter.

“Before they start doing this in art, they just think, ‘Physics has to do with planes,’” explains Sharma. “It doesn’t occur to them that physics is actually all around us, and science is all around us. Anyone can be a scientist. It’s not just someone who studies science.”

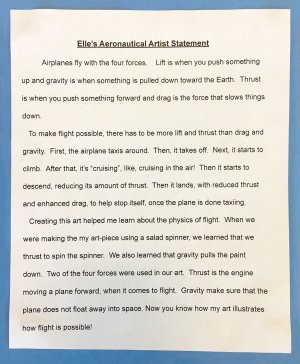

Use Artist Statements for Assessment

Have your students show their understanding through an artist statement. “Artist statements are a great way for artists to share what they’ve done in their artwork, why they’ve done it, the materials they’ve used, and how it has changed their thinking or deepened their understanding,” explains Quinter. “It’s a way for students to present their artwork and their understanding through the artwork.”

To create an artist statement:

Step One: Begin by showing your students real artists statements. Have them analyze what does and does not make a good artist statement, and ask them what they should include in theirs.

Step Two: Have your students critique each other’s artist statements: What word choices did they use? How did they make their artist statement come alive? In what ways did they describe their artwork?

“The whole point is for the teachers to facilitate rather than direct,” says Sharma. “It would be easy for us to say, ‘A good artist statement has three sentences that describe the art, and they say something like this….’ But in order for them to have ownership over their own learning, we say, ‘What makes this artist statement good? What do you think?’”

For each art experiment, every student writes their own artist statement, and they use those critiques to inform their collaborative artist statement for their final product.

“The learning objectives for the artist statement are twofold,” explains Sharma. “The first one is a content-based learning target, explaining how the the forces work together to make an airplane fly. And the second is our literacy learning target, using descriptive words and strong adjectives to describe their art.”

Jessica Wodatch, Two Rivers’ executive director, believes, “It’s exciting to see kids who have been stuck on a concept, and all of a sudden they get it. The arts are another avenue to help kids understand something, and they make the classroom much richer.”