Firing Up Student Engagement With STEAM Electives

Enrichment classes like toy making and candy chemistry combine fun with serious content in science, technology, engineering, the arts, and math.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Overview

At Walter Bracken STEAM Academy, a Title 1 magnet school in urban Las Vegas, Nevada, they've turned enrichment classes into Explos. Explos, short for explorations, are 50-minute, hands-on, enrichment classes that teachers create based on student interest. These classes -- on topics from costume engineering to bubble gum science -- give students choice, engage them, and allow teachers to get creative with developing Science, Technology, Engineering, Art, and Math (STEAM) curriculum.

Explo classes:

- Tie into STEAM curriculum

- Are offered at the end of the day, three times a year

- Meet two times a week for four weeks

- Are non-graded

- Are multi-grade level

"When the kids are able to choose what they're going to learn about, they're more engaged, and they're more likely to pursue that topic outside of class,” says Katie Decker, Walter Bracken's principal. "It's all about engaging students and getting them excited about learning."

How It's Done

Step 1: Choose an Explo Topic

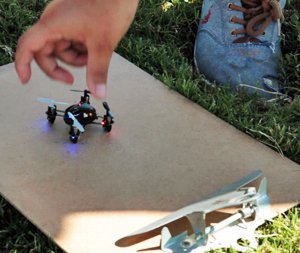

Topic ideas come from teachers' passions. They get to bring their hobbies into the classroom. Past Explos have included The Art of Street Performing, Decoding the Rubic's Cube, The Usefulness of Drones, Girls Just Wanna Engineer Fun, and Can-struction (construction principles taught with cans of food, which are later donated).

For ideas on STEAM Explo topics, Decker recommends looking at:

- Steve Spangler Science

- We Are Teachers' "STEM/STEAM Lessons, Activities and Ideas" Pinterest board

- Teacher Pay Teachers

- Content Searches

- Google Images

- Science in a Nutshell

- GEMS Kits

Step 2: Pitch Your Explo to Your Students

The Explos with the most interest are offered as multiple classes. If one teacher's Explo doesn't get enough votes, someone else's Explo gets a chance. This encourages all teachers to create a captivating pitch so that students will choose their course.

"It's all about selling it to the kids," says Vicky Zblewski, a Walter Bracken fourth-grade teacher.

To create a good pitch, Zblewski recommends:

- Make sure it's something that captures your students’ interest.

- Create a good title.

- Create a fun and exciting two-sentence course description.

To make the voting process unbiased, don't mention:

- The teacher's name in the course title or description

- Food in the course description

Example Explo Titles and Descriptions

Here are two Explo titles and descriptions that Bracken teachers created and pitched to their students:

- Bubble Gum Science: Whether you like to chew it, pop it, snap it, or chomp it, bubble gum is a fun treat! Have you ever wondered how it is made or who invented it? Learn the science behind gum in the Bubble Gum Explo!

- Mousetrap Mania: Calling all engineers! A mouse is loose in the school, we need the best mousetrap builders to safely catch Squeaky and return him to his family. No mice will be harmed in this explo.

Step 3: Set Up Student Voting

Bracken teachers send their Explo titles and descriptions to Principal Decker, and she makes a sign-up sheet for each grade. The sheet includes a space for the student's name, teacher, and room number. She lists each course title in one column, and the course description in the adjacent column.

Decker advises:

- When presenting students with their options, only show them the choices for their grade level.

- Send the sign-up sheet home with your students, and give them at least two weeks to pick their first, second, and third choices.

- Include space at the bottom of the sheet for parents to give feedback on the Explos.

After students hand in their sign-up sheets, teachers review the choices and send them to Decker, who divides the students evenly among all staff members.

Step 4: Get Creative With Your Curriculum

"You don't have to have a standardized mainstream curriculum to teach the standards," explains Klaus Friedrich, a Walter Bracken fifth-grade teacher. "I don't have to spend two hours on math out of the math book to teach math. When I teach about drones in the Drone Explo, I'm still going to teach math. That opens up the diversity of curriculum that normally you wouldn't find in a lot of schools."

In Zblewski's Toy-ology Explo class, students learn about engineering concepts. "When you are building toys, you don't necessarily think that that's educational,” she observes, “but they're using their engineering skills. They have to plan it out, they have to think about measuring and putting the wheels and dowels on equally. In education, curriculum sometimes can be scripted, and these exploration classes give us the freedom to come up with a different idea."

Step 5: Fund Your Explo

Zblewski's Toy-ology students are making their own toys using Kleenex boxes, water bottle caps, straws, glue, and markers, and they're planning their toy designs with pencil and paper. Making an Explo doesn't have to be expensive.

To get funding and materials, Decker recommends:

- Ask parents and staff for donations.

- Ask if you can borrow items from other schools.

- Reach out to your local community.

- Run a crowdfunding campaign on DonorsChoose.org.

- Collect Box Tops for Education.

- Apply for small grants from the Rotary Club, McDonald's, Women's Junior League, and local organizations

Step 6: Survey the Students at the End of an Explo

Once students finish an Explo, Bracken teachers give their students a survey to find out what they enjoyed about the class, what other existing Explos they would want to take, and what new subjects they want to learn about that aren't yet offered. This helps inform the teachers in designing their Explos for the next semester.

When creating a survey, Decker recommends:

- Simplify the survey for younger students.

- Give younger students the list of classes to help them fill out the survey.

- Use SurveyMonkey to save on paper.

Step 7: Give Yourself Time

"The biggest challenge that I'm faced with as an educator," acknowledges Friedrich, "is traditional thinking in teaching." He explains that schools will often try a new practice for a year, look at the results, and if it's not meeting their expectations, move on to a new practice. "The hardest part is they need to give it time," adds Friedrich. "It takes years to see it grow and get better. It has taken eight or nine years to get this to be where it is."