Silence Is Not Golden: Speaking Up and Coming Out as a Teacher

Recalling his reaction to student hate messages, a former high school teacher considers how he could have reframed the incident as a teachable moment.

Your content has been saved!

Go to My Saved Content.Editor‘s note: This blog describes a hostile act and contains language that some might find disturbing and offensive. We generally avoid such representations on Edutopia. However, it would be difficult for the blogger to make his point without this level of impact, and we believe it is a point worth making.

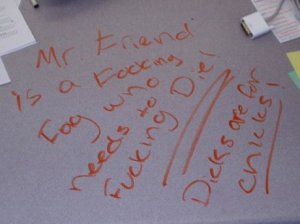

Years ago, I taught high school in a small suburban community in Florida. After my then-boyfriend substituted in my classes one day, my classroom was vandalized with threatening, offensive messages on the whiteboard, my desk, and the overhead projector and its screen. The contents of my desk were strewn across the room, and some personal property I had brought to my workspace was defaced. Overall, very little physical damage was done, but the event seriously shook my nerves.

Maintaining Silence

I somehow managed to teach that day. I don't remember what we were working on, but I went through the motions. That still amazes me. What now infuriates me is this: I didn't tell my students what had happened, what it did to me, why I was so shaken by it or why it happened in that community. The only residual sign of trouble was the pile of disheveled papers collected on one side of the room -- that, and my persistent nothing-to-see-here demeanor.

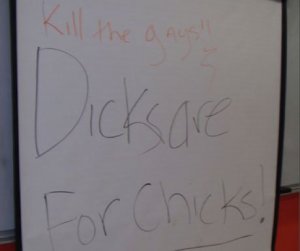

My demeanor almost broke when I decided to use the overhead projector. I had already removed the threatening graffiti from the projector's surface so that I could use the machine for class. I never thought to check the screen, which had stayed retracted. I pulled it down to use it, with a full class of students watching. Rather than a blank, white screen, I found this scrawled in permanent marker: "Kill the gays!! Dicks are For Chicks!"

I immediately rolled the screen back up and used the whiteboard instead, apologizing for "the glare." The glare. I acted as though the threats -- the actual problem that was hurting me and disrupting my ability to function and feel safe – weren't there. Of all the "teachable moments" I've encountered, this one most needed to be taught. Yet it was the one I tried hardest to cover up because I was uncomfortable with being gay at my own school.

Why Do We Hide?

Looking back after ten years' experience as a teacher and as a human, I see that my reaction to the event did nothing to help me, my students or the school community learn from the situation. Rather than discuss issues of acceptance and equality, I ignored them. Ultimately, I was afraid to discuss or reveal my sexuality because Florida law provides no protection against termination due to sexual orientation and because the town where I taught was inhospitable to LGBT people. My own response to the vandalism -- silence -- reinforced the unspoken rule in the community that gay people were not to be discussed.

I know now that the only one I was hiding anything from was myself. Students had already figured out I was gay. They saw through my denial and avoidance, turning my efforts at concealing my identity into a highlighter, pointing out exactly what I didn't want them to see.

As a result, I was blindly broadcasting an aura of fear, of shame, through the very efforts that were intended to accept and nurture students like me, who needed support and acknowledgement in a potentially hostile environment. Because I never brought up my sexuality on campus, I continued the discrimination. By hiding, I silently expressed my fear and added to the problem I feebly wanted to protect students from. I was trying to make sure that students felt safe in my classroom. Instead, I showed them that even I was not.

Making the Minority More Visible

I've spent time -- on a journal about teaching, on my personal blog and in conference presentations -- talking about bringing the outside world inside the classroom walls. But I've not publicly considered the classroom as a workplace in which I should be comfortable being myself. Looking back on the vandalism, I see now that the "outside world" also includes the personal. Pretending that my personal life and my educational practice can be separated denies the validity and relevance of each.

For those of us in the invisible minority of sexual orientation, we have an obligation to speak out. I don't mean for any "agenda" or political assertion. I mean for visibility. We must make our existence less invisible, less silent. Greater identification will help those in unforgiving environments feel a connection with others like them and show the majority that we exist and want to be heard.

My sexuality is not a liability, and it should not be a reason to fire me. Instead, my sexuality offers perspective and experience, which my students deserve to know about. To teach as myself, I must let my students see who I am. I must use my voice to end the silence.

So let me relive the day my classroom was vandalized. Let me show that I can shake with combined anger and embarrassment. That I can shed tears from being overwhelmed and caught off guard. Let me point to the vandalism and say I live in a society that allowed this to happen. Let me end my silence and commit to using my voice. Let me come out to my classes. Because no matter how loud the silence may have felt, using my voice makes me louder.

Speaking Out as Teachers

Each of us needs to speak out. If we are trying to prepare our students for life in a world full of diversity and variety, our classrooms cannot present a false image of homogeneity. We need to openly and compassionately discuss our differences, and we start by acknowledging these differences exist.

I challenge you to come out to your students about something that sets you apart but that isn't obvious. Choose something you never imagined you could be open about with your students. Maybe you're colorblind. Maybe you secretly love the Twilight series but don't usually admit it. Maybe you have a chronic medical condition that you have to carefully manage. Maybe you're an atheist. Whatever it is, come out to your students. See how it feels, especially in the moments right before and right after the disclosure. See how students react. See how it can create an opportunity to respectfully discuss, to share and to learn.

An extended version of this article originally appeared on Hybrid Pedagogy as part of a collection about race, gender, disability, and sexuality in education.